Reading Group -- Semantically Equivalent Adversarial Rules for Debugging NLP Models

(Originally written for the Stanford NLP Blog)

Robustness is a central concern in engineering. Our suspension bridges need to stand against strong wind and so it won’t collapse like the Tacoma Narrows Bridge [video]. Our nuclear reactors need to be highly fault tolerant so that Fukushima Daiichi incident won’t happen in the future [link].

In the second post, we will focus on this paper:

Ribeiro, Marco Tulio, Sameer Singh, and Carlos Guestrin. “Semantically equivalent adversarial rules for debugging nlp models.” Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Vol. 1. 2018.

When we increasingly become reliant on a type of technology – suspension bridges, nuclear power, or in this case: NLP models, we must raise the level of trust we have in this technology. Robustness is precisely the requirement we need to place on such systems.

Early work from Jia & Liang (2017)1 shows that NLP models are not immune to small negligible-by-human perturbation in text – a simple addition or deletion can break the model and force it to produce nonsensical answers. Other work such as Belinkov & Bisk 2, Ebrahimi et al.3 showed a systematic perturbation that is to simply drop or replace a character is sufficient to break a model. Introducing noise to sequence data is not always bad: ealier work done by Xie et al.4 shows that training machine translation or language model with word/character-level perturbation (noising) actually improves performance.

However, it is hard to call these perturbed examples “adversarial examples” in the original conception of Ian Goodfellow5. This paper proposed a way to define an adversarial examples in text through two properties:

Semantic equivalence of two sentences: $\text{SemEq}(x, x’)$

Perturbed label prediction: $f(x) \not= f(x’)$

In our discussion, people point out that from a linguistic point of view, it is very difficult to define “semantic equivalence” because we don’t have a precise and objective definition of “meaning”. This is to say that even though two sentences might elicit the same effect for a particular task, they do not need to be synonymous. A more nuanced discussion of paraphrases in English can be found in What Is a Paraphrase? [link] by Bhagat & Hovy (2012). In this paper, semantic equivalence is operationalized as what humans (MTurkers) judged to be “equivalent”.

Semantically Equivalent Adversaries (SEAs)

Ribeiro et al. argue that only a sequence that satisfies both conditions is a true adversarial example in text. They translate this criteria into a conjunctive form using an indicator function:

$\text{SEA}(x, x’) = \unicode{x1D7D9}[\text{SemEq}(x, x’) \wedge f(x) \not= f(x’)] \label{1}$

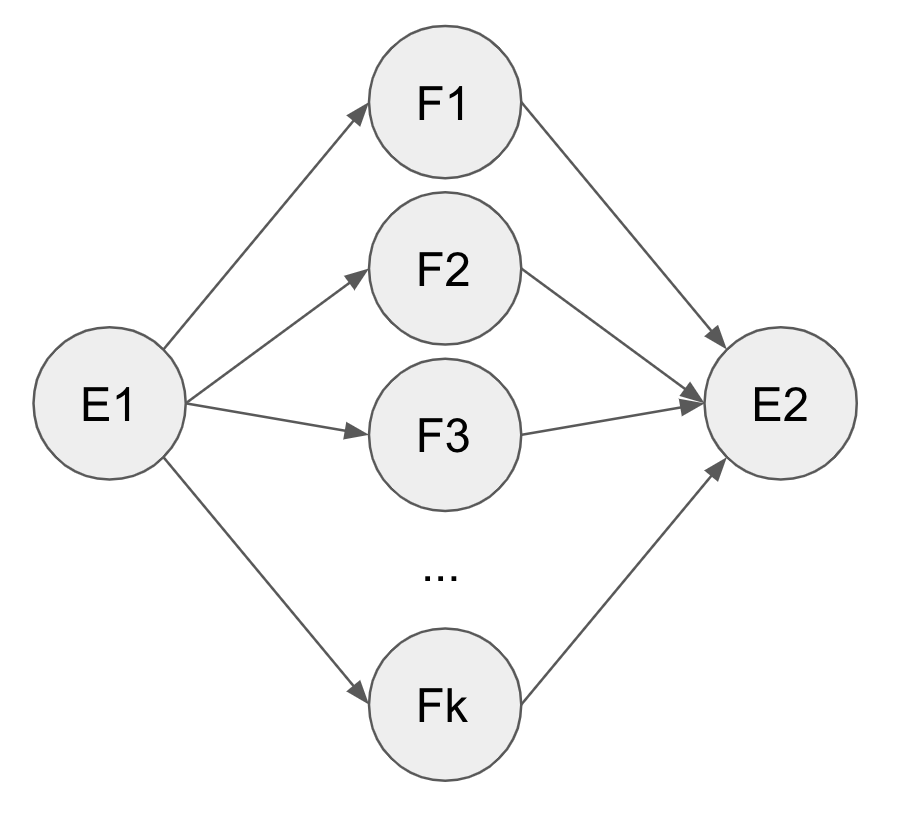

In this paper, semantic equivalence is measured by the likelihood of paraphrasing, defined in multilingual multipivot paraphrasing paper from Lapata et al. (2017)6. Pivoting is a technique in statistical machine translation proposed by Bannard and Callison-Burch (2005)7: if two English strings $e_1$ and $e_2$ can be translated into the same French string $f$, then they can be assumed to have the same meaning.

The pivot scheme is depicted by the generative model on the left, which assumes conditional independence between $e_1$ and $e_2$ given $f$: $p(e_2 \vert e_1, f) = p(e_2 \vert f)$ . Multipivot is depicted by the model on the right: it translates one English sentence into multiple French sentences, and translate back to generate the parphrase. The back-translation of multipivoting can be a simple decoder average – each decoder takes a French string, and the overall output probability for the next English token is the weighted sum of the probability of every decoder.

Paraphrase Probability Reweighting

Assuming the unnormalized logit from the paraphrasing model is $\phi(x’ \vert x)$, and suppose $\prod_x$ is the set of paraphrases that the model could generate given $x$, then the probability of a particular paraphrase can be written as below:

$p(x’ \vert x) = \frac{\phi(x’ \vert x)}{\sum_{i \in \prod_x} \phi(i \vert x)}$

Note in the denominator, all sentences being generated (including generating the original sentence) share the probability mass. If a sentence has many easy-to-generate paraphrases (indicated by high $\phi$ value), then $p(x \vert x)$ will be small, as well as all other $p(x’ \vert x)$. Dividing $p(x’ \vert x)$ by $p(x \vert x)$ will get a large value (closer to 1). As for a sentence that is difficult to paraphrase, $p(x \vert x)$ should be rather large compared to $p(x’ \vert x)$, then this ratio will provide a much smaller value.

Based on this intuition, Ribeiro et al. proposed to compute a semantic score $S(x, x’)$ as a measure of the paraphrasing quality:

$S(x, x’) = \min(1, \frac{p(x’ \vert x)}{p(x \vert x)})$

$\text{SemEq}(x, x’) = \unicode{x1D7D9}[S(x, x’) \geq \tau]$

A simple schema to generate adversarial sentences that satisfy the Equation 1 is: ask the paraphrase model to generate paraphrases of a sentence $x$. Try these paraphrases if they can change the model prediction: $f(x’) \not = f(x)$.

Semantically Equivalent Adversarial Rules (SEARs)

SEAs are paraphrases that are generated for each text sequence. In this step, authors lay out steps to convert these local SEAs to global rules (SEARs). The rule defined in this paper is a simple discrete transformation $r = (a \rightarrow c)$. The example for $r = (movie \rightarrow film)$ can be $r$(“Great movie!”) = “Great film!”.

Given a pair of text $(x, x’)$ where $\text{SEA}(x, x’) = 1$, Ribeiro et al. select the minimal contiguous span of text that turn $x$ into $x’$, include the immediate context (one word before and/or after the span), and annotate the sequence with POS (Part of Speech) tags. The last step is to generate the product of combinations between raw words and their POS tags. A step-wise example is the follow:

Step 1: (What -> Which)

Step 2: (What color -> Which color)

Step 3: (What color -> Which color), (What NOUN -> Which NOUN), (WP color -> Which color), (What color -> WP color)

Since this process is applied for every pair of $(x, x’)$, and if we assume humans are only willing to go through $B$ rules, then Ribeiro et al. propose to filter the candidates such that $\vert R \vert \leq B$. The criteria would be:

- High probability of producing semantically equivalent sentences: this is measured by a population statistic $E_{x \sim p(x)}[\text{SemEq(x, r(x))}] \geq 1 - \delta$. Simply put, by applying this rules, most $x$ in the corpus can be translated to semantically equivalent paraphrases. In the paper, $\delta = 0.1$.

- High adversary count: rule $r$ must also generate paraphrases that will alter the prediction of the model. Additionally, the semantic similarity should be high between paraphrases. This can be measured by $\sum_{x \in X} S(x, r(x)) \text{SEA}(x, r(x))$.

- Non-redundancy: rules should be diverse and cover as many $x$ as possible.

To satisfy criteria 2 and 3, Ribeiro et al. proposed a submodular optimization objective, which can be solved with a greedy algorithm with a theoretical guarantee to a constant factor off of the optimum.

$\max_{R, \vert R \vert <B} \sum_{x \in X} \max_{r \in R} S(x, r(x)) \text{SEA}(x, r(x))$

The overall algorithm is described below:

Experiment and Validation

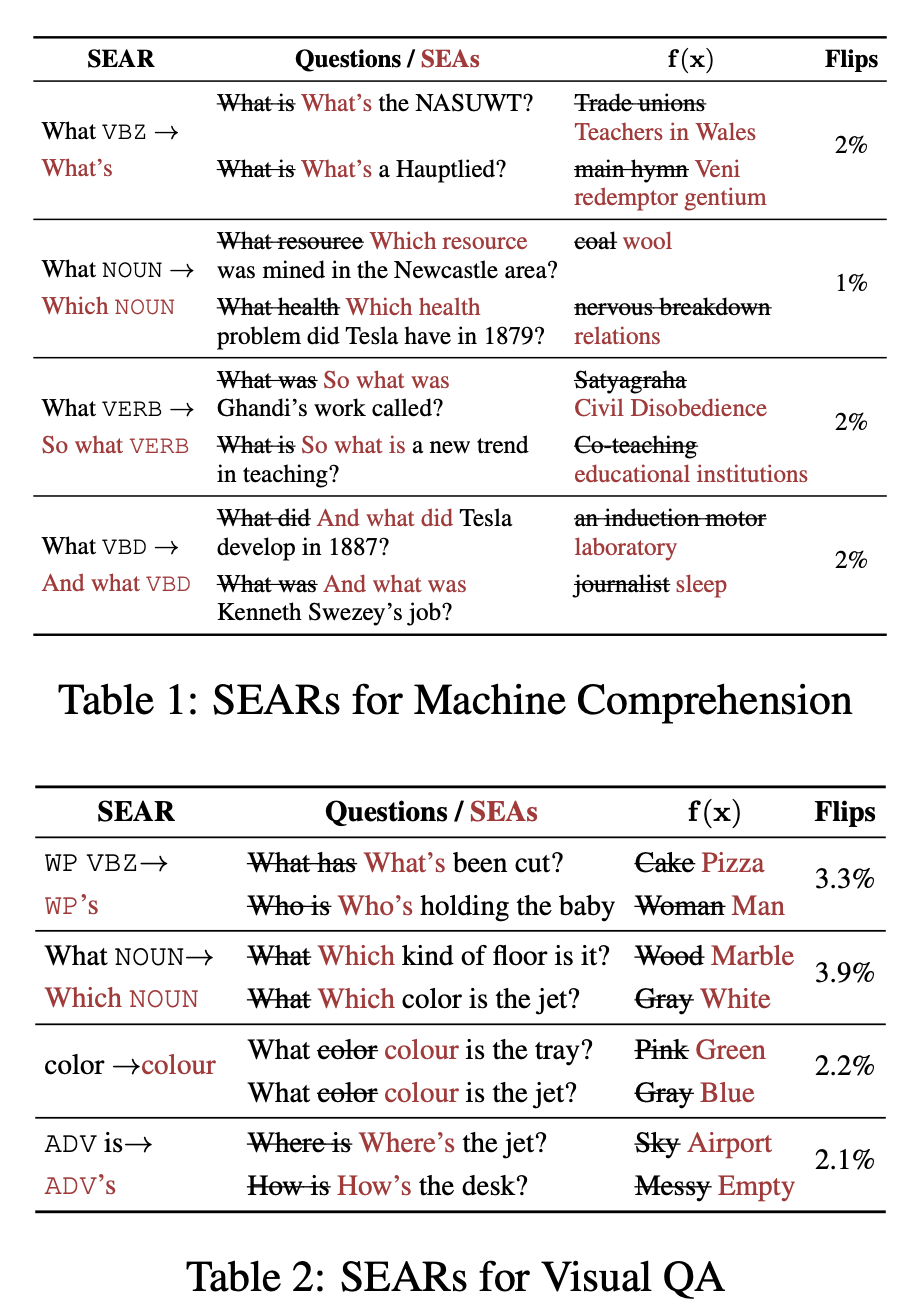

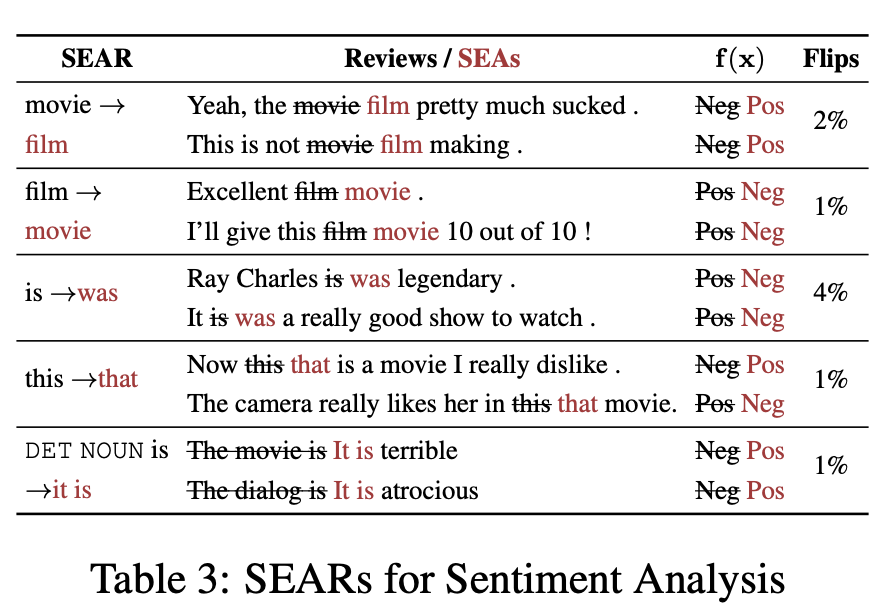

The key metric Ribeiro et al. measure is the percentapge of Flips, defined as in the validation set, how many instances are predicted correctly on the validation data, but predicted incorrectly after the application of the rule.

The comment on this metric during discussion is that it does not indicate how many examples are there that are affected by this rule. For example, a rule that changes “color” to “colour” might have a Flips rate of 2.2% in VQA dataset, but this might only be that in the validation set of VQA, only 2.2% of instances contain the word color, so this rule has a 100% rate of success at generating adversarial examples.

The paper shows some really good discrete rules that can generate adversarial text examples:

Human-in-the-loop

Ribeiro et al. conducted experiments on humans. Bringing humans into the loop can serve two purposes: humans can judge if rules can actually generate paraphrases (beyond the semantic scoring model provided by Lapata et al.); humans can judge if the perturbations incurred by rules are actually meaningful.

They first judge the quality of SEA: For 100 correctly predicted instances in the validation set, they create three sets of comparison: 1). completely created by human MTurkers, referred as humans; 2). purely generated by the paraphrasing model described above as SEA; 3). Generate SEA by the algorithm, but replace the $S(x, x’)$ criteria with human judgment.

They show that SEA narrowly beats human (18% vs. 16%), but combining with human judgments, HSEA outperforms human by a large margin (24% vs. 13%).

Then they evaluate the global rules SEARs. This time, they invite “experts” to use an interactive web interface to create global rules. They define experts as students, faculties who have taken one graduate-level NLP or ML class. Stricly speaking, experts should have been linguistic students.

Experts are allowed to see immediate feedback on their rule creation: they know how many instances (out of 100) are perturbed by their rule, and how many instances have their prediction label perturbed. In order to have a fair comparison, they are asked to create as many rules as they want, but select 10 as the best. Also each expert is given roughly 15 minutes to create rules. They were also asked to evaluate SEARs and select 10 rules that most perserve semantic equivalence.

The results are not surprising. SEARs are much better at getting high flip percentage. Combined effort between human and machine is higher than the individual. They also compared the number of seconds on average it takes an expert to create rules vs. evaluating rules created by the machine.

Finally, the paper shows to fix those bugs, they can simply perturb the training set using these human-accepted rules, and they are able to reduce the percentage of error from 12.6% to 1.4% on VQA, and from 12.6% to 3.4$ on sentiment analysis.

Wrap up

This paper uses paraphrasing models as a way to measure semantic similarity and generating semantically equivalent sentences. As is mentioned in text, machine translation based paraphrasing perturbs the sentence only locally, while humans generate semantically equivalent adversaries with more significant perturbations.

Another limitation is that gradient-based adversarial example generation is directional and precise, while method proposed by this paper seems to be simple trial-and-error approach (keep generating paraphrases until one paraphrase perturbs the model prediction).

After careful human evaluation, only 4 rules for VQA and 16 rules for sentimen are accepted by humans as acceptable rules – a rather small yield compared to the effort spent at generating these rules. In the algorithm’s defense, these rules do cover more than 10% of the validation set, a nontrivial coverage.

This paper provides a clear framework and proposes clear properties that adversarial text examples should abide. This definition is very compatible with adversarial examples in computer vision. However, this framework only covers a specific type of adversarial examples. An obvious adversarial example not covered by this method would be operations such as adding or deleting sentences, which is important at attacking QA models.

-

Jia, Robin, and Percy Liang. “Adversarial examples for evaluating reading comprehension systems.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.07328 (2017). ↩

-

Belinkov, Yonatan, and Yonatan Bisk. “Synthetic and natural noise both break neural machine translation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.02173(2017). ↩

-

Ebrahimi, Javid, et al. “HotFlip: White-Box Adversarial Examples for Text Classification.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.06751 (2017). ↩

-

Xie, Ziang, et al. “Data noising as smoothing in neural network language models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.02573 (2017). ↩

-

Goodfellow, Ian J., Jonathon Shlens, and Christian Szegedy. “Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples (2014).” arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572. ↩

-

Mallinson, Jonathan, Rico Sennrich, and Mirella Lapata. “Paraphrasing revisited with neural machine translation.” Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Volume 1, Long Papers. Vol. 1. 2017. ↩

-

Colin Bannard and Chris Callison-Burch. 2005. Paraphrasing with bilingual parallel corpora. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 597–604, Ann Arbor, Michigan. ↩