Bayesian Neural Decoding:

— Using Visual Questions to Control Caption Generation

Preface

In the past 2 years, controlling generative models (such as GANs and VAEs) have been widely studied in the Computer Vision literature. The idea is that once these large capacity neural network models learn the data manifold of millions of images, it has “inherent” knowledge about the world (in the form of understanding “skin tone”, “hair style” in celebrity faces, or “brightness”, “camera angles” for bird images). Then through some post-training manipulation for GAN/VAE, we can bring these disentangled aspect of the image out to the surface.

Figure 1: (a) from OpenAI GLOW demo; (b) from ICLR 2020 paper: On the "steerability" of generative adversarial networks.

Despite such impressive result, controlling generative models in text has been far more difficult. Unlike images, where humans have an intuitive idea on what to control: rotation angle, brightness, blueness of picutres; age, beard, hair color for faces, we have no intuitive idea on what to control for text beyond simple ideas like sentiment or tense1. Follow-up work like Lample et al.2 leveraged the domain where the data is collected to add additional attributes like gender, race, age, and interests (like music, book, movie, etc.), and trained a neural network from scratch conditioned on these attributes.

Although these efforts have greatly expanded our capability to manipulate text, they are not designed to discover the “learned disentangled representation” by modeling the data distribution. Also, any work that requires an attribute classifier is inherently unscalable.

In this post, I will show you how we can control the output from a model that is trained on a joint distribution of images and text. It builds up a conditional distribution $P(\mathbf{w}\vert\mathbf{i})$ where we can control the generation of text by systematically varying the image input to this distribution. We do not rely on additional attribute classifiers and allow the control of text generation through a simple visual question inputted by the user.

Since conditioning on images allows us to (again) form an intuitive understanding of what aspect of text we want to control, we can use our understanding in images (various objects, behaviors) as ground truth to dictate what we want in text. Our proposed method also only uses a trained generative model, which means any aspect we are able to control, is inherently learned by the generative model by learning from the conditional distribution.

Previous works that studied this setting (and used methods somewhat similar to ours) mostly focused on the concept of “granularity” – how detailed can the text be 34. This is only one attribute of text to control. In our work, we will try to control the model to generate text on an infinite amount of attributes. The work described by this post is my new paper with Reuben Cohn-Gordon and Chris Potts5.

Figure 2: Examples from applying our method to a SoTA 6-layer encoder-decoder Transformer with 55M parameters image captioner trained on the MS COCO dataset. The base caption shows what the Transformer originally would have outputted without our method (last column). The penultimate column (Issue-sensitive caption) shows what our method would produce. We can produce captions that answer questions about objects and attribute of objects.

By asking visual questions, such as “what color is the sky”, we control the image captioner to focus on the peculiar nature of this photo (that this is a black & white photo). Instead of describing what is the scene of this picture (“airplane taking off”), the caption model describes the meta-level information of this picture: (“a black and white photo of an airplane”).

Examining controllable text generation in a joint (image, text) domain solves the problem of not knowing what aspect of text to control, and dense annotations in image datasets allows us to quickly verify how well we can control the generated text. I will then describe how we control the caption generation by asking a question.

Controlling via RSA: A Simple Tour

The Rational Speech Act (RSA) framework is a Psycholinguistic framework that models how human would (rationally) communicate information. Given a set of images (let’s assume each image is fully represented by a list of attributes such as {blue cap, mountain}), RSA is a Bayesian game where the goal is to pick an attribute from the set to best represent this image, in the presence of other “distracting” images. It’s like in a cop show, where the police lines up suspects and the witness needs to identify who committed the crime.

Source: New Yorker; University of Michigan, Law School.

If you were asked to say a word so that the police can pick out number 5 (but you are not allowed to say numbers), you probably wouldn’t say “a man”, nor would you say “khaki pants”. The best word you can pick (assuming you are rational) is “baseball cap” because that uniquely identifies number 5. RSA is created to emulate this thought process – when you have a group of images, you want to pick the word that best represents it (so that it’s distinguishing the target image from the rest).

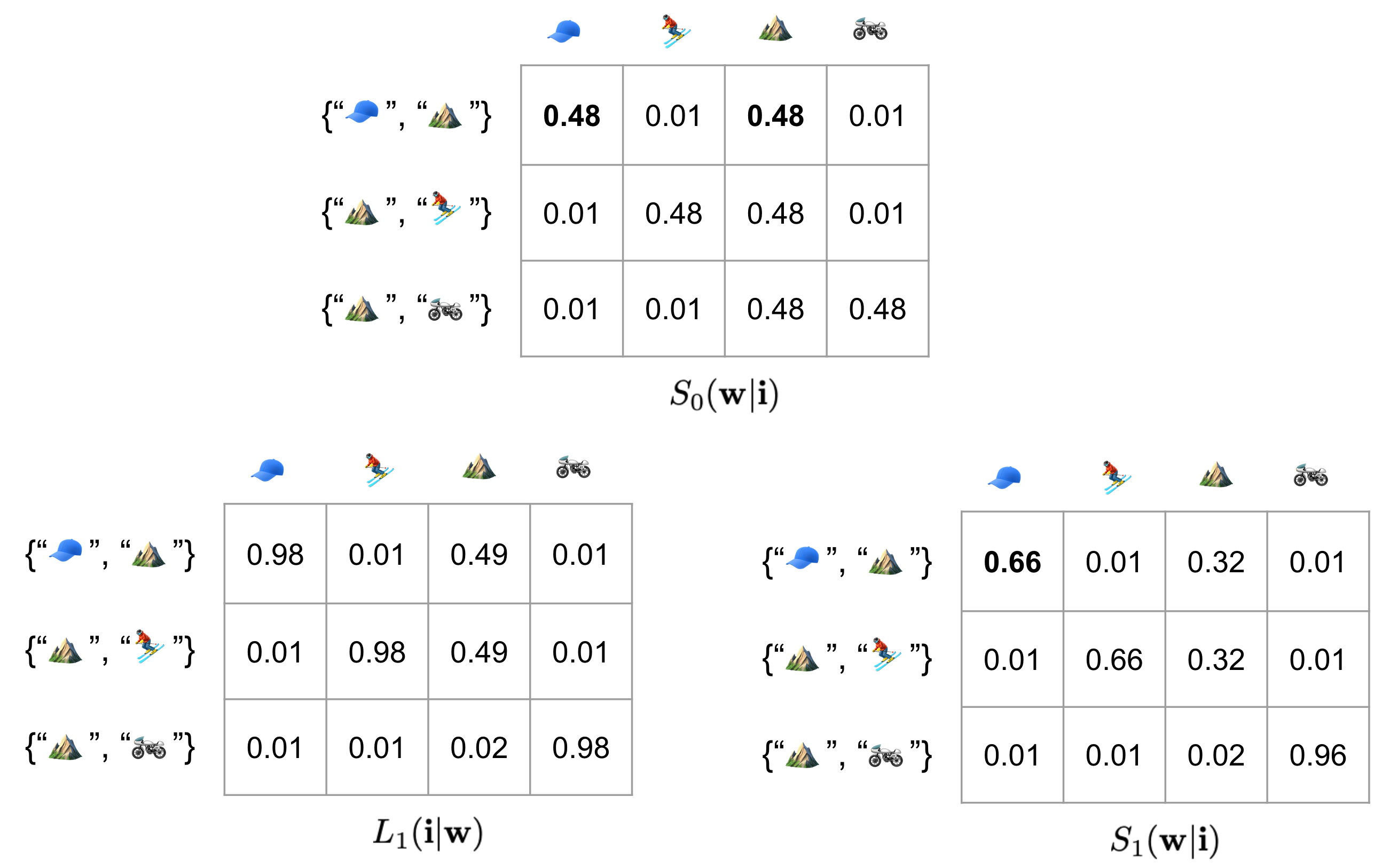

The computational process that RSA describes that achieves this communicative goal is through normalizing the probability table twice. We start with $S_0(\mathbf{w} \vert \mathbf{i})$, a row-stochastic probability matrix (probabilities in a row sum up to 1) where the rows are “images”, represented as a list of objects, and the columns are the objects we can pick to describe the image.

Figure 3: A simple RSA computing process.

Without considering the communicative goal, just using $S_0$ (which is often our maximum-likelihood trained model that directly approximates our data distribution), for the first row, we will choose either baseball cap or mountain. However, if we want to uniquely identify it (to a police officer, or to anyone who’s “listening”) against the other two rows, we would realize that the other two rows also have mountains. What’s unique about the first row is the baseball cap.

In order to fulfill our intuition, more formally, we first normalize the columns of $S_0$, to turn it from a row-stochastic matrix to a column-stochastic matrix, arriving at $L_1$ distribution, and then normalize again to turn $L_1$ back to a row-stochastic matrix. This process describes the model considering “reasonable” alternatives of its choices and then decide what to select to achieve its best unambiguous outcome. We can see in bold number that $S_1$ will choose baseball cap to describe the first image, contrasting two other images.

More formally, these two computations can be described as:

\[\begin{align*} L_1(\mathbf{i}|\mathbf{w}) &= \frac{S_0(\mathbf{w}|\mathbf{i}) P(\mathbf{i})}{P(\mathbf{w})} = \frac{S_0(\mathbf{w}|\mathbf{i}) P(\mathbf{i})}{\sum_{i \in \mathcal{I}} S_0(\mathbf{w}|\mathbf{i}) P(\mathbf{i})} \\ S_1(\mathbf{w}|\mathbf{i}) &= \frac{L_1(\mathbf{i}|\mathbf{w}) P(\mathbf{w})}{P(\mathbf{i})} = \frac{L_1(\mathbf{i}|\mathbf{w}) P(\mathbf{w})}{\sum_{w \in \mathcal{V}} L_1(\mathbf{i}|\mathbf{w}) P(\mathbf{w})} \\ \end{align*}\]In RSA books/papers, you often see the simplified version (skipping the normalization term):

\[\begin{align*} L_1(\mathbf{i}\vert\mathbf{w}) &\propto S_0(\mathbf{w}|\mathbf{i}) P(\mathbf{i}) \\ S_1(\mathbf{w}\vert\mathbf{i}) &\propto L_1(\mathbf{i}|\mathbf{w})P(\mathbf{w}) \end{align*}\]More detailed tutorial of RSA can be found in here. As you can see, by directly applying RSA, we are already able to control one aspect of text generation: how detailed do we want the text to be?

Figure 4: Decoding result from Vedantam et al.'s work. Even though they are not applying a full RSA solution, their suppressor-emitter beam search (where they also normalize across distractors) is equivalent to computing RSA normalization.

RSA + VQA: Is Our Caption Question-Aware?

Let’s set our goal straight: first of all, we want to control the caption generation through a question. Second of all, we want the generated caption to address the question.

Given a target image and a question: $(\mathbf{i}, \mathbf{q})$, we can directly apply any pre-trained VQA model to get an answer. Given a lot of images and the same question, we can get a lot of answers. Some of these answers are different from the answer for the target image, some are the same. For example, with our target image: {blue baseball cap, mountain}, we can ask the following visual question: Does the person wear a baseball cap?, where the answer is Yes or No.

Given this answer, we can partition a list of images into two groups: images where the person is wearing a baseball cap, and images where the person is NOT wearing a baseball cap. Note that the question can be extremely general and ask about various aspects of the image.

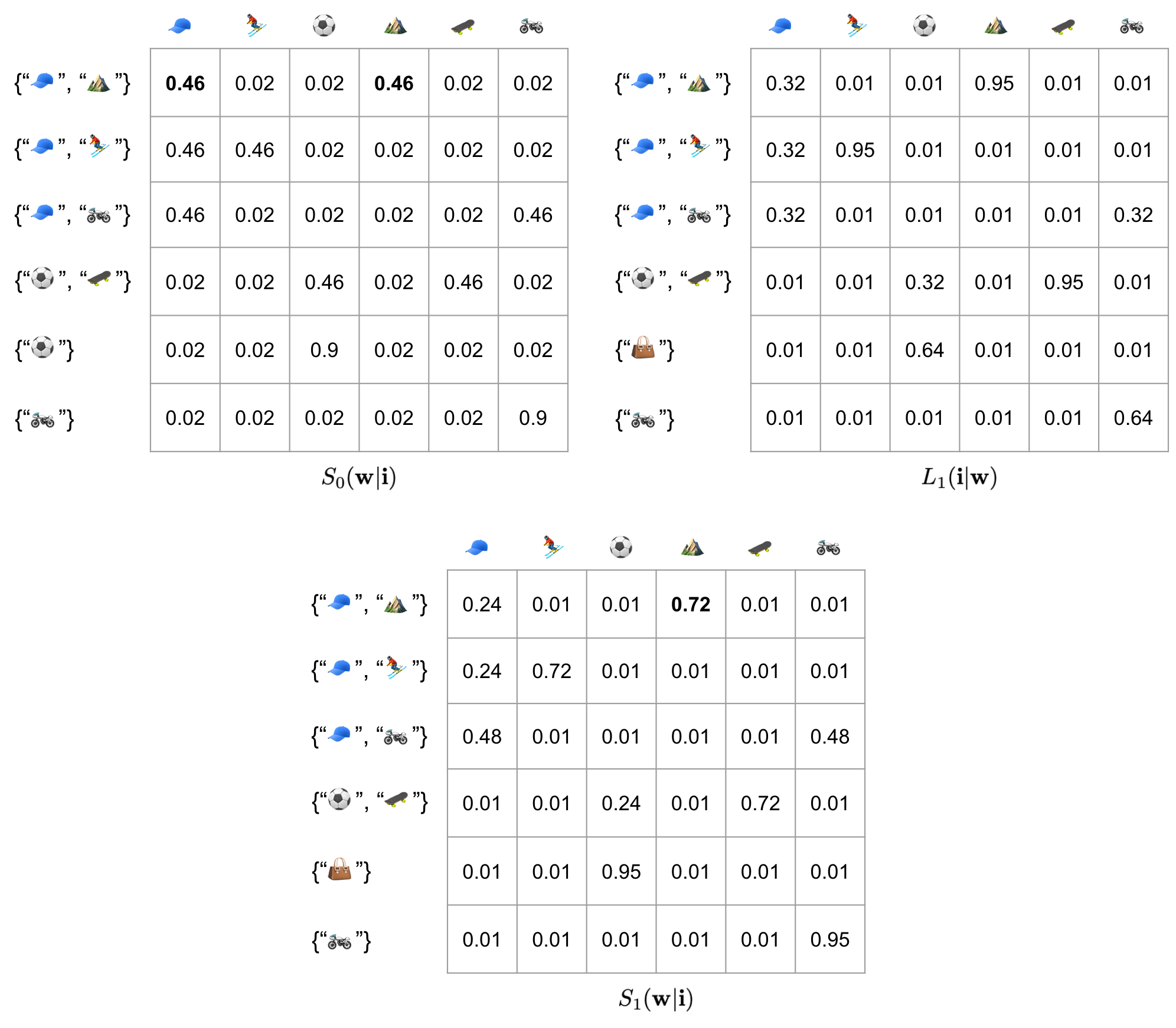

Suppose we happen to select these 6 images from a larger group of images. First three images have baseball cap, the next three do not. Can we just naively apply RSA and hope the item we pick will be about the baseball cap? The answer is unfortunately no. Before RSA, the caption model will randomly choose between baseball cap and mountain. After RSA, it will choose mountain, which is worse.

Figure 5: Directly applying RSA is NOT question-aware (or issue-sensitive, as defined in our paper).

OK. We ran into a problem. The problem is very simple to understand – even though our VQA model partitioned 6 images into two cells (top 3 rows and bottom 3 rows), the RSA computation is unaware of this (cell structure). What it does is treating all 5 other images (rows) as distractors and try to find what’s unique about the target image (first row) against all else, which is the mountain.

Luckily, a solution has already been worked out by Kao et al. 6 The idea is pretty simple, why not just add up the probability within the cell (across the column) after computing $L_1$ probability matrix? More formally, this corresponds a different $S_1$:

\[\begin{align*} U_1^{\mathbf{C}}(\mathbf{i}, \mathbf{w}, \mathbf{C}) &= \log \Big( \sum_{\mathbf{i}' \in \mathcal{I}}\delta_{\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{i})=\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{i}')} L_1(\mathbf{i}'|\mathbf{w}) \Big) \\ S_1^{\mathbf{C}}(\mathbf{w} \vert \mathbf{i}, \mathbf{C}) &\propto \text{exp} \big(\alpha U_1^{\mathbf{C}}(\mathbf{i}, \mathbf{w}, \mathbf{C}) - \text{cost}(\mathbf{w}) \big) \end{align*}\]This formula redefines the pragmatic listener matrix $L_1$ as an informative utility $U_1^{\mathbf{C}}$, and compute $S_1$ probability matrix proportional to it. In the RSA literature, this is often referred to as the QuD-RSA (QuD: Question-under-Discussion). If we visualize this process with actual probability numbers, here’s the result:

Figure 6: We show the computational process of QuD-RSA.

As you can see, what we really did is just add up along the column for the original $L_1$ matrix, and then normalize over the row for the target image. This allows our RSA output to be issue-sensitive (question-aware). But wait wait wait, something is not right here! If you actually looked very closely at the $S_1^\mathbf{C}$ result, you’d realize what the RSA picked out is still wrong – it would randomly choose between skiing and mountain. What the heck is going on?

So, what QuD-RSA actually does is that, it creates an “equivalence class” between all images in the same cell. It converts the original objective, which is to “pick an item to best describe target image” to “pick an item to best describe the target cell”. QuD-RSA is designed to ignore the differences between within-cell images. Since picking mountain or skiing (neither appeared in the distractor images) would already best identify the target cell, there is no additional incentive to pick baseball cap. Suffice to say this is not what we want.

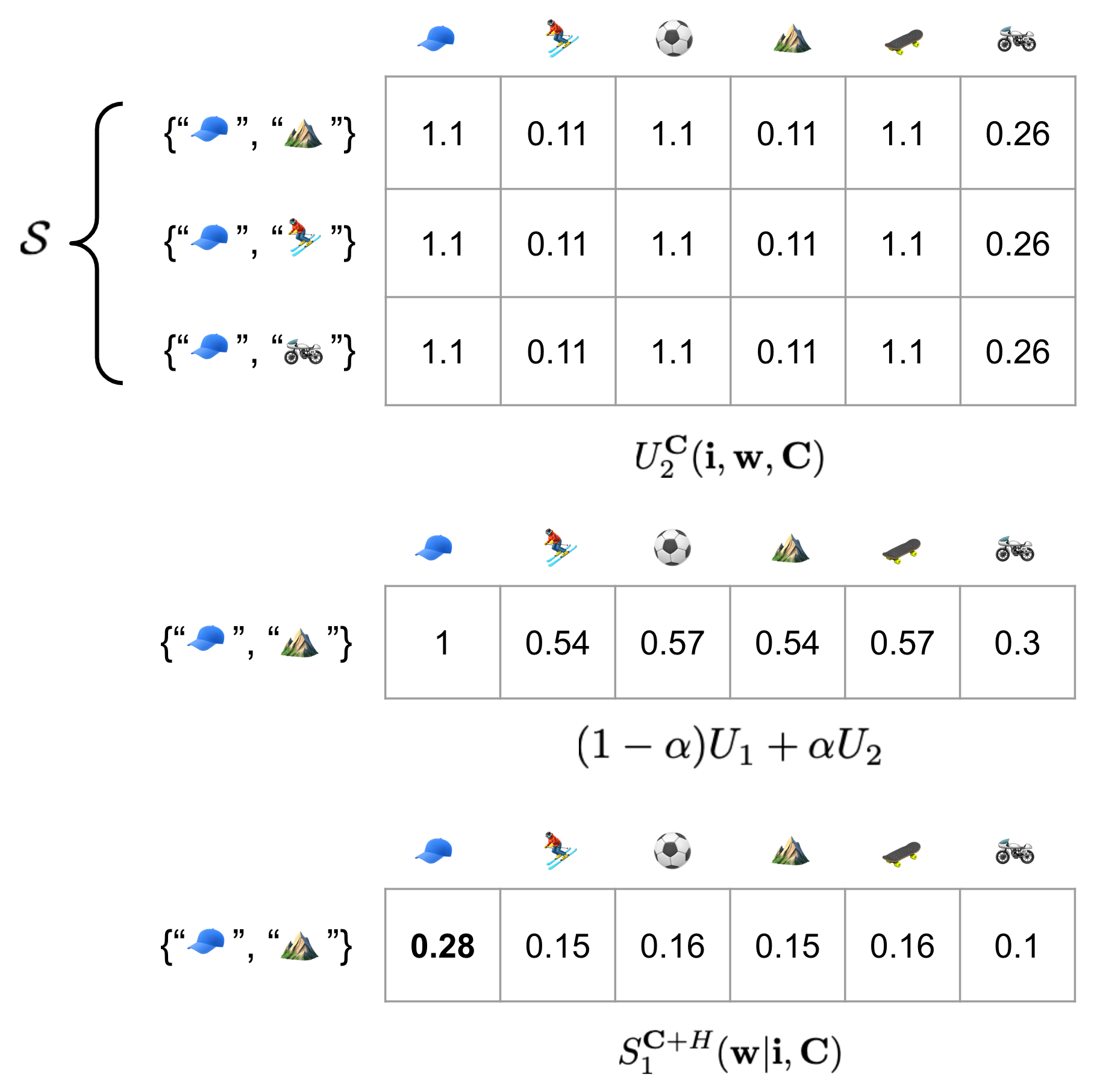

This last ingredient allows us to add a pressure to the $S_1$ matrix to select items that are shared amongst all images within the cell. Intuitively, since all images within the target cell share the same answer to the VQA question, whatever attribute/object in the image allows that answer will have a higher chance to appear in the resulting caption. This ingredient we choose to add is called Shannon entropy, where flatter distribution (more uniform distribution) will have a higher entropy, and peakier distribution will have a lower entropy. Since baseball cap is shared among all three images in the target cell, it will have the highest entropy.

More formally, we can write it out to combine both $U_1$ and $U_2$, with a balancing hyper-parameter $\beta$ that decides between how much weight we want to put on either utility:

\[\begin{align*} U_2(\mathbf{i}, \mathbf{w}, \mathbf{C}) &= H(L_1(\mathbf{i}'|\mathbf{w}) \cdot \delta_{\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{i})=\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{i}')}) \\ S_1^{\mathbf{C}+H}(\mathbf{w} \vert \mathbf{i}, \mathbf{C}) &\propto \text{exp} \big( \alpha ((1-\beta)U_1 + \beta U_2) -\text{cost}(\mathbf{w}) \big) \end{align*}\]And computationally it can be visualized as:

Figure 6: We show the computational process of QuD-Entropy-RSA.

Now the story for generating issue-sensitive (question-aware) captions is complete. With the added entropy reward, the $S_1$ matrix will finally pick baseball cap as the answer to What is the person wearing?.

Evaluating on Birds (CUB)

(TBD)

-

Hu, Z., Yang, Z., Liang, X., Salakhutdinov, R., & Xing, E. P. (2017, August). Toward controlled generation of text. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning-Volume 70 (pp. 1587-1596). JMLR. org. ↩

-

Lample, G., Subramanian, S., Smith, E., Denoyer, L., Ranzato, M. A., & Boureau, Y. L. (2018). Multiple-attribute text rewriting. ↩

-

Vedantam, R., Bengio, S., Murphy, K., Parikh, D., & Chechik, G. (2017). Context-aware captions from context-agnostic supervision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 251-260). ↩

-

Mao, J., Huang, J., Toshev, A., Camburu, O., Yuille, A. L., & Murphy, K. (2016). Generation and comprehension of unambiguous object descriptions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 11-20). ↩

-

Nie, Allen, Reuben Cohn-Gordon, and Chris Potts. “Pragmatic Issue-Sensitive Image Captioning .” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.14451 (2020). ↩

-

Kao, J. T., Wu, J. Y., Bergen, L., & Goodman, N. D. (2014). Nonliteral understanding of number words. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(33), 12002-12007. ↩